Tagged: Britain

The Eclipse of the Ottoman Empire – The End of a Medieval Reality

Many see the First World War as the end of the Prussian monarchy, or the birth of Communist Russia, but overlook the eclipse of one of the world’s greatest empires, that of the Ottomans. Since the defeat of Christian Byzantium at the sack of Constantinople, Europe’s south-eastern flank would be dominated by the world of Islam. This reality – born in the middle-ages – would persist until 1918. The First World War marked the end of an age and the beginning of another in many respects, but perhaps the defeat of the Ottoman Empire is the most drastic example of this historic watershed.

While Europe was trapped in centuries of dark ages, the world of Islam had been culturally and technologically ahead. Muslim cities in the medieval period possessed advanced infrastructure and architecture, the accomplishments of their universities and libraries meant they were the world’s best in many areas of science and industry. Once North Africa and much of the Middle East had belonged to the Romans, but by the Medieval period these lands had fallen to the Caliphate. Byzantium was the Medieval continuation of the Eastern Roman Empire. The Western Roman Empire had been overrun by barbarian hordes, its title reused by the first Holy Roman Emperor, the Frankish King Charlemagne. To medieval Europe, the Muslim threat was embodied by the Ottoman Turks, a reality which continued into the Renaissance and the Age of Discovery, and indeed until the Great War. The Turks were the face of Islam from the defeat of the Byzantines at Battle of Manzikert in 1071 until 1918; only recently have the Arabs been recognised as the head of Muslim civilization.

Constantinople had at one point been the greatest city in Europe. It had been the capital of Byzantium, which had remained a Christian entity since the Eastern Roman Emperor Constantine ruled from its seat. But the city fell to the Turks in 1453. If this caused anxiety for the Christian monarchs of eastern and southern Europe, the next century would cause considerably more.

Following Turkish conquest of Damascus in 1516 and their subsequent advances on Egypt and Arabia, the janissary armies of the Ottomans turned on Hungary, which had become the great eastern christian bastion after the fall of Constantinople. Following the Battle of Mohacs in 1526, Hungary was overrun. The Ottoman Empire was now at its height, and covered more territory than that of Rome. One could hardly blame scholars at the time for concluding that the future would belong to the Islamic world, and much of the continent would inevitably belong to the Sultan. This inclination nearly became reality when the Ottomans besieged Vienna in 1529, and when they did so again in 1683.

The capitulation of the Ottomans: a drawn-out affair

Yet the Ottoman Empire would inevitably falter and collapse. Its armies and navies, however formidable, were overextended – needing to maintain frontiers in Central Europe, the Crimean, the Mediterranean, the Red Sea, and the Near East where the Ottomans were challenged by the Persians. This geographic challenge of the area is one I explore further in The Geopolitical Realities of Eurasia. Its challenges were not insurmountable, but as a single entity the Ottoman Empire was overly centralised. Whereas European division was in many ways the continent’s strength, as competing states would challenge one-another to explore and expand, one foolish Sultan could do more damage to the Ottoman Empire that any lone European monarch or pope could ever hope to accomplish. From 1566 on, there reigned thirteen incompetent sultans in succession, sealing the empire’s doom.

It was the slow retreat of the Turks that caused the European powers to look towards the Balkans and consider who would benefit from the Turkish collapse. It was this power struggle, known as the ‘Eastern Question,’ that among other things motivated a Habsburg Archduke to parade himself and his nation’s power in Sarajevo, whose death in turn triggered the Great War that would divide the lands that still remained under Turkish control.

The First World War severed the Arab provinces from the sultan’s grip. Ironically, early twentieth-century Arabian warfare was remarkably similar to that of fourteenth-century Europe, allowing the medieval-military historian Thomas Edward Lawrence to exploit the Arabic advantages. Of course, this legendary figure did not engineer the Arabic revolt on his own, his own account of the events in The Seven Pillars of Wisdom, was admitted to be part myth. Furthermore, the Arabs would not get what they had fought for, as the ever imperialist states of Britain and France would divide the Middle East between themselves. This, after-all, was inadvertently why the whole war had begun.

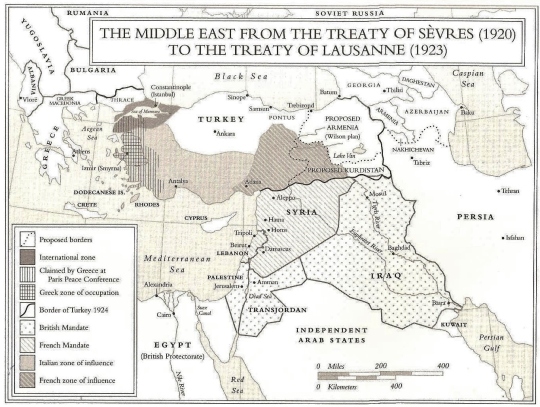

Lawrence’s companion, Prince Feisal, spoke to the delegation in the Paris Peace Conference while Lawrence translated. They must have looked an odd pair, especially the Englishman who had donned the white robes and gold sashing normally reserved for a senior sheik. Feisal said that the Arabs wanted self-determination, and while he was prepared to exempt Lebanon and Palestine from this demand, the rest of the Arab world should be given independence as the British and French had promised. When the French reminded Lawrence that their forces had fought in Syria during the crusades, Lawrence replied: “Yes, but the Crusaders had been defeated and the Crusades had failed.” Against the wishes of Lawrence and the Arabs, Britain was also determined to get a piece of the Middle East. Forced to prevent the non-colonial aspirations of the American President Woodrow Wilson by co-operating, the two imperial rivals came to a quick compromise; Britain would get Mesopotamia (Iraq) and Palestine, while France would get Syria and Lebanon. The Arabian Peninsula did not concern the imperial powers much, probably because all those ‘miles of sand’ were not of much value at the time.

The British motives were clear. For long they had supported the Ottoman Empire to keep the eastern end of the Mediterranean safe for their shipping, but now they needed an alternate hold in the area. This motivation highlights the geopolitical value of the area. Where once the Muslims had dominated the Silk Road which provided medieval Europe with eastern riches, now the British needed to protect its trade route to India. Of course, the Industrial Revolution had created new interests in the area’s oil, but the old geopolitical motives persisted as well.

Constantinople was promised to the Russian Czar at one point in the war, but the concessions made by the Bolsheviks cancelled that agreement. While the once-great Ottoman Empire was divided, Constantinople would remain in the hands of its owners since 1453. It was occupied by the allied powers (unofficially at first), but this would not survive the determination of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk. Remarking at the presence of allied warships in Constantinople’s harbour, he proclaimed: “As they have come, so they shall go.”

A modern Turkey would rise from the ashes

As a young officer in the Turkish military, Atatürk oversaw Austria’s annexation of Bosnia, and Bulgaria secession from Turkish influence. The Balkan wars of 1912 and 1913 result in the Ottomans loss of Albania and Macedonia, and Libya had been lost to the Italians. By 1914, the European portion of the Ottoman Empire, which had once stretched far into Hungary, was almost wholly gone – all that remained was an enclave in Thrace. Throughout the Great War, Atatürk remained the only undefeated Ottoman general. His reputation was made at Gallipoli, the same battle where many allied reputations were destroyed. In his eyes Turkey was defeated not by greater armies, but by greater civilization. Henceforth, he would ensure Turkey would adopt European-style culture and politics. Indeed, Turkey remains a secular state to this day.

Atatürk sent Inonu Ismet, a trusted general, to the Paris Peace Conference to negotiate. He was instructed to achieve an independent Turkey, and as a good soldier he intended to achieve just this by any means. Turkey’s new borders included almost all the Turkish speaking territories of their former Ottoman Empire, but the fact was the empire had ended and a new very different state had been birthed. It was truly the end of an age.

Works Cited

Anderson, Scott. Lawrence in Arabia. New York: Random House, 2013.

Kaplan, Robert D. The Revenge of Geography. New York: Random House, 2012.

MacMillan, Margaret. Paris 1919. New York: Random House, 2002.