The New Great Game: America’s longest war

The United States of America has decided to endure its longest war. It has made this decision not because it believes it will prevail against a native insurgency – the United States has grander geopolitical interests in mind. By continuing to occupy Afghanistan, America is ensuring it is not overlooked in this century’s ‘New Great Game’.

Trump does not possess much interest in governing, he never has. On most of foreign policy, he has boasted of deferring decisions “to the generals”. While separating an ill-informed, uninterested, impulsive president from perilous decision-making is undoubtedly beneficial to the United States’ interests, it must be noted that the consequence is a markedly more imperialistic state with a renewed interest in realpolitik. This observation is clearest when considering the American administration’s decision to continue America’s longest war.

The geopolitical importance of Central Asia

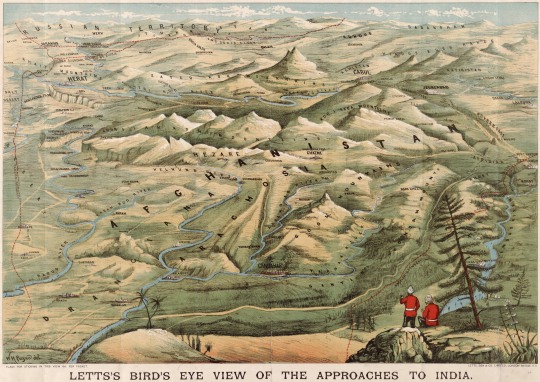

To India’s north, the Himalayas serve as a wall protecting India from foreign invasion. To the northeast, the Burmese jungles also present harsh enough conditions to shield India from advancing armies. It is from the northwest that India is most vulnerable. Here lies the Persian-Afghan plateau (a gradual incline rather than a divisive mountain range). It is from here that India has faced invading Greeks, Persians, and Mongols, because it is easier to march armies across a plain than over mountains or through jungle.

During the nineteenth century, the British Empire’s Indian holdings stood at the foot of the Persian-Afghan plateau. British officials, peering across this expanse, were concerned by an expanding Russian empire, fearing that Russian invaders would use the Afghan route to seize the crown jewel of the empire. Meanwhile, St Petersburg feared British commercial and military inroads into Central Asia. As such, Afghanistan was the key to security for each rival power – securing Afghanistan would counter each empire’s vulnerability. This rivalry was dubbed ‘the great game’.

The great game example illustrates a geopolitical reality of Eurasia: it is from Central Asia that all other Eurasian powers are most vulnerable. This reality was opined on by the geopolitical scholar Halford John Mackinder, who presented a paper titled ‘The Geographical Pivot of History’ to the Royal Geographical Society in 1904, and later published his book Democratic Ideals and Reality: A Study in the Politics of Reconstruction, which restated his ideas, in 1919. He summarizes his theory with overly quoted and simplistic maxim:

Who rules East Europe commands the Heartland [Central Asia]:

Who rules the Heartland [Central Asia] commands the World-Island [Eurasia]:

Who rules the World-Island [Eurasia] commands the World.

The first line of the maxim must be contextualized. Democratic Ideals and Reality was published during the Paris Peace Conference, and was meant to influence the statesmen at Versailles in their division of Europe after World War I – (the sub-title ‘A Study in the Politics of Reconstruction’ makes the book’s purpose clear). The Russian, Austrian, and Ottoman Empires had all collapsed, and Mackinder was making the case that it was a “vital necessity that there should be a tier of independent states between Germany and Russia”. This was a political goal rather than a geopolitical observation.

The second two lines are Mackinder’s maxim are more mechanical. Mackinder observed the world at a time when railways were opening Central Asia to trade, commerce, and conquest. Where once the area had been controlled exclusively by horse-riding nomads, it would soon be controlled by an industrialized power. Just as the Mongols had conquered all of Eurasia (and consequently terrorized medieval Europe) so too would Russia – and Mackinder was warning Britain and France that their navies would no longer allow them to command the World.

In one way, Mackinder’s maxim was proved right. After World War 2, Russia was able to project power globally because it controlled Central Asia, and most of Eurasia. Had it been preoccupied in Central Asia (for example, if it had to send armies to Siberia to counter Japan), Russia would have lost World War II. Instead, Russia could focus all its efforts on defeating, Germany, and in World War II’s aftermath, Russia asserted itself as one of the world’s great powers. By controlling Central Asia, Russia won World War II, and thereafter could project power as far away as Cuba.

On the other hand, Mackinder’s maxim was proved to be overreaching. Russia, even by controlling Central Asia, never commanded all of Eurasia, and never the World – it lost the Cold War. But it must be remembered that throughout the Cold War Russia remained vulnerable in Central Asia, China was often more of a rival than an ally, and in the Cold War’s final days Russia fought a prolonged War in Afghanistan. Moreover, I do not rely on Mackinder’s maxim as an empirical truth, rather it simply illustrates the geopolitical reality: it is from Central Asia that all other Eurasian powers are most vulnerable.

Modern geopolitics in Central Asia

The tectonic forces of geopolitics are reawakening in Central Asia. Where once the Soviet Union had dominated the region, new forces are asserting themselves: the rising powers of China and India, a Russia that hopes to claw back its Central Asian losses, and an invigorated Iran. China, in particular, deserves some further analysis.

Whereas Russia has always coveted access to the ocean, China is a similarly sized land power with a coastline in both the tropic and temperate zones. Therefore, according to Mackinder, China is theoretically in the world’s most geopolitically advantageous position, in that it can both control Central Asia and project power from Eurasia.

China is asserting itself in the former Soviet sphere of influence. It has become the leading trading partner for all the former Soviet republics (apart from Uzbekistan), as well as the region’s largest investor. Currently China is spearheading its “belt and road” initiative, in which China plans to invest billions of dollars in Central Asian infrastructure – ostensibly to project economic power.

The American Top Brass’s realpolitik

The result of all this is clear. The balance of power in Central Asia is changing. China is asserting itself. Russia is vulnerable. Iran (who no longer has the regional rival Iraq to worry about) is projecting power as far away as Syria and Yemen – it could just as easily turn east. Whichever power controls Central Asia (in the end, most likely China), can then control Eurasia.

Serendipitously, it is at this time that America finds itself with an outpost right in the heart of Central Asia: Afghanistan. Why would America squander the opportunity to have its thumb on the scale during this ‘new great game’? Another president may have overridden his (or her) generals’ focus on the geopolitical forces in favour of domestic or even global humanitarianism, but this president is happy to cede such decisions to the military. The result is a renewed realism. Security is paramount. Any opportunity to influence the dynamic forces of Central Asian geopolitics must be seized because he who rules the Heartland commands the World-Island, and he who rules the World-Island commands the World.

Works Cited

The Economist, What is China’s belt and road initiative? https://www.economist.com/blogs/economist-explains/2017/05/economist-explains-11

The Economist, Xi Jinping and Vladimir Putin behave like the best of buddies, https://www.economist.com/news/china/21725611-suspicion-between-russia-and-china-runs-deep-xi-jinping-and-vladimir-putin-behave-best

Kaplan, Robert D., The Revenge of Geography. New York: Random House, 2012.

Mackinder, Sir Halford J., Democratic Ideals and Reality: A Study in the Politics of Reconstruction. Washington D.C.: National Defense University Press, 1942.