Category: History – post 1900

The New Great Game: America’s longest war

The United States of America has decided to endure its longest war. It has made this decision not because it believes it will prevail against a native insurgency – the United States has grander geopolitical interests in mind. By continuing to occupy Afghanistan, America is ensuring it is not overlooked in this century’s ‘New Great Game’.

Trump does not possess much interest in governing, he never has. On most of foreign policy, he has boasted of deferring decisions “to the generals”. While separating an ill-informed, uninterested, impulsive president from perilous decision-making is undoubtedly beneficial to the United States’ interests, it must be noted that the consequence is a markedly more imperialistic state with a renewed interest in realpolitik. This observation is clearest when considering the American administration’s decision to continue America’s longest war.

The geopolitical importance of Central Asia

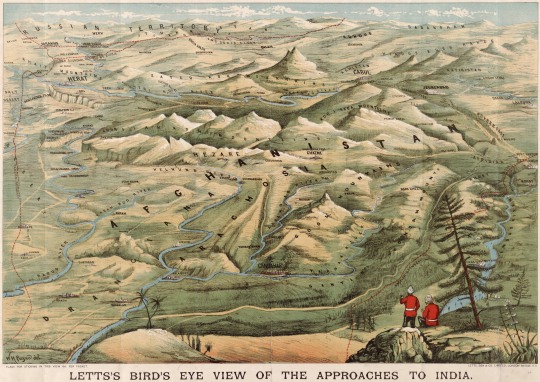

To India’s north, the Himalayas serve as a wall protecting India from foreign invasion. To the northeast, the Burmese jungles also present harsh enough conditions to shield India from advancing armies. It is from the northwest that India is most vulnerable. Here lies the Persian-Afghan plateau (a gradual incline rather than a divisive mountain range). It is from here that India has faced invading Greeks, Persians, and Mongols, because it is easier to march armies across a plain than over mountains or through jungle.

During the nineteenth century, the British Empire’s Indian holdings stood at the foot of the Persian-Afghan plateau. British officials, peering across this expanse, were concerned by an expanding Russian empire, fearing that Russian invaders would use the Afghan route to seize the crown jewel of the empire. Meanwhile, St Petersburg feared British commercial and military inroads into Central Asia. As such, Afghanistan was the key to security for each rival power – securing Afghanistan would counter each empire’s vulnerability. This rivalry was dubbed ‘the great game’.

The great game example illustrates a geopolitical reality of Eurasia: it is from Central Asia that all other Eurasian powers are most vulnerable. This reality was opined on by the geopolitical scholar Halford John Mackinder, who presented a paper titled ‘The Geographical Pivot of History’ to the Royal Geographical Society in 1904, and later published his book Democratic Ideals and Reality: A Study in the Politics of Reconstruction, which restated his ideas, in 1919. He summarizes his theory with overly quoted and simplistic maxim:

Who rules East Europe commands the Heartland [Central Asia]:

Who rules the Heartland [Central Asia] commands the World-Island [Eurasia]:

Who rules the World-Island [Eurasia] commands the World.

The first line of the maxim must be contextualized. Democratic Ideals and Reality was published during the Paris Peace Conference, and was meant to influence the statesmen at Versailles in their division of Europe after World War I – (the sub-title ‘A Study in the Politics of Reconstruction’ makes the book’s purpose clear). The Russian, Austrian, and Ottoman Empires had all collapsed, and Mackinder was making the case that it was a “vital necessity that there should be a tier of independent states between Germany and Russia”. This was a political goal rather than a geopolitical observation.

The second two lines are Mackinder’s maxim are more mechanical. Mackinder observed the world at a time when railways were opening Central Asia to trade, commerce, and conquest. Where once the area had been controlled exclusively by horse-riding nomads, it would soon be controlled by an industrialized power. Just as the Mongols had conquered all of Eurasia (and consequently terrorized medieval Europe) so too would Russia – and Mackinder was warning Britain and France that their navies would no longer allow them to command the World.

In one way, Mackinder’s maxim was proved right. After World War 2, Russia was able to project power globally because it controlled Central Asia, and most of Eurasia. Had it been preoccupied in Central Asia (for example, if it had to send armies to Siberia to counter Japan), Russia would have lost World War II. Instead, Russia could focus all its efforts on defeating, Germany, and in World War II’s aftermath, Russia asserted itself as one of the world’s great powers. By controlling Central Asia, Russia won World War II, and thereafter could project power as far away as Cuba.

On the other hand, Mackinder’s maxim was proved to be overreaching. Russia, even by controlling Central Asia, never commanded all of Eurasia, and never the World – it lost the Cold War. But it must be remembered that throughout the Cold War Russia remained vulnerable in Central Asia, China was often more of a rival than an ally, and in the Cold War’s final days Russia fought a prolonged War in Afghanistan. Moreover, I do not rely on Mackinder’s maxim as an empirical truth, rather it simply illustrates the geopolitical reality: it is from Central Asia that all other Eurasian powers are most vulnerable.

Modern geopolitics in Central Asia

The tectonic forces of geopolitics are reawakening in Central Asia. Where once the Soviet Union had dominated the region, new forces are asserting themselves: the rising powers of China and India, a Russia that hopes to claw back its Central Asian losses, and an invigorated Iran. China, in particular, deserves some further analysis.

Whereas Russia has always coveted access to the ocean, China is a similarly sized land power with a coastline in both the tropic and temperate zones. Therefore, according to Mackinder, China is theoretically in the world’s most geopolitically advantageous position, in that it can both control Central Asia and project power from Eurasia.

China is asserting itself in the former Soviet sphere of influence. It has become the leading trading partner for all the former Soviet republics (apart from Uzbekistan), as well as the region’s largest investor. Currently China is spearheading its “belt and road” initiative, in which China plans to invest billions of dollars in Central Asian infrastructure – ostensibly to project economic power.

The American Top Brass’s realpolitik

The result of all this is clear. The balance of power in Central Asia is changing. China is asserting itself. Russia is vulnerable. Iran (who no longer has the regional rival Iraq to worry about) is projecting power as far away as Syria and Yemen – it could just as easily turn east. Whichever power controls Central Asia (in the end, most likely China), can then control Eurasia.

Serendipitously, it is at this time that America finds itself with an outpost right in the heart of Central Asia: Afghanistan. Why would America squander the opportunity to have its thumb on the scale during this ‘new great game’? Another president may have overridden his (or her) generals’ focus on the geopolitical forces in favour of domestic or even global humanitarianism, but this president is happy to cede such decisions to the military. The result is a renewed realism. Security is paramount. Any opportunity to influence the dynamic forces of Central Asian geopolitics must be seized because he who rules the Heartland commands the World-Island, and he who rules the World-Island commands the World.

Works Cited

The Economist, What is China’s belt and road initiative? https://www.economist.com/blogs/economist-explains/2017/05/economist-explains-11

The Economist, Xi Jinping and Vladimir Putin behave like the best of buddies, https://www.economist.com/news/china/21725611-suspicion-between-russia-and-china-runs-deep-xi-jinping-and-vladimir-putin-behave-best

Kaplan, Robert D., The Revenge of Geography. New York: Random House, 2012.

Mackinder, Sir Halford J., Democratic Ideals and Reality: A Study in the Politics of Reconstruction. Washington D.C.: National Defense University Press, 1942.

The Eclipse of the Ottoman Empire – The End of a Medieval Reality

Many see the First World War as the end of the Prussian monarchy, or the birth of Communist Russia, but overlook the eclipse of one of the world’s greatest empires, that of the Ottomans. Since the defeat of Christian Byzantium at the sack of Constantinople, Europe’s south-eastern flank would be dominated by the world of Islam. This reality – born in the middle-ages – would persist until 1918. The First World War marked the end of an age and the beginning of another in many respects, but perhaps the defeat of the Ottoman Empire is the most drastic example of this historic watershed.

While Europe was trapped in centuries of dark ages, the world of Islam had been culturally and technologically ahead. Muslim cities in the medieval period possessed advanced infrastructure and architecture, the accomplishments of their universities and libraries meant they were the world’s best in many areas of science and industry. Once North Africa and much of the Middle East had belonged to the Romans, but by the Medieval period these lands had fallen to the Caliphate. Byzantium was the Medieval continuation of the Eastern Roman Empire. The Western Roman Empire had been overrun by barbarian hordes, its title reused by the first Holy Roman Emperor, the Frankish King Charlemagne. To medieval Europe, the Muslim threat was embodied by the Ottoman Turks, a reality which continued into the Renaissance and the Age of Discovery, and indeed until the Great War. The Turks were the face of Islam from the defeat of the Byzantines at Battle of Manzikert in 1071 until 1918; only recently have the Arabs been recognised as the head of Muslim civilization.

Constantinople had at one point been the greatest city in Europe. It had been the capital of Byzantium, which had remained a Christian entity since the Eastern Roman Emperor Constantine ruled from its seat. But the city fell to the Turks in 1453. If this caused anxiety for the Christian monarchs of eastern and southern Europe, the next century would cause considerably more.

Following Turkish conquest of Damascus in 1516 and their subsequent advances on Egypt and Arabia, the janissary armies of the Ottomans turned on Hungary, which had become the great eastern christian bastion after the fall of Constantinople. Following the Battle of Mohacs in 1526, Hungary was overrun. The Ottoman Empire was now at its height, and covered more territory than that of Rome. One could hardly blame scholars at the time for concluding that the future would belong to the Islamic world, and much of the continent would inevitably belong to the Sultan. This inclination nearly became reality when the Ottomans besieged Vienna in 1529, and when they did so again in 1683.

The capitulation of the Ottomans: a drawn-out affair

Yet the Ottoman Empire would inevitably falter and collapse. Its armies and navies, however formidable, were overextended – needing to maintain frontiers in Central Europe, the Crimean, the Mediterranean, the Red Sea, and the Near East where the Ottomans were challenged by the Persians. This geographic challenge of the area is one I explore further in The Geopolitical Realities of Eurasia. Its challenges were not insurmountable, but as a single entity the Ottoman Empire was overly centralised. Whereas European division was in many ways the continent’s strength, as competing states would challenge one-another to explore and expand, one foolish Sultan could do more damage to the Ottoman Empire that any lone European monarch or pope could ever hope to accomplish. From 1566 on, there reigned thirteen incompetent sultans in succession, sealing the empire’s doom.

It was the slow retreat of the Turks that caused the European powers to look towards the Balkans and consider who would benefit from the Turkish collapse. It was this power struggle, known as the ‘Eastern Question,’ that among other things motivated a Habsburg Archduke to parade himself and his nation’s power in Sarajevo, whose death in turn triggered the Great War that would divide the lands that still remained under Turkish control.

The First World War severed the Arab provinces from the sultan’s grip. Ironically, early twentieth-century Arabian warfare was remarkably similar to that of fourteenth-century Europe, allowing the medieval-military historian Thomas Edward Lawrence to exploit the Arabic advantages. Of course, this legendary figure did not engineer the Arabic revolt on his own, his own account of the events in The Seven Pillars of Wisdom, was admitted to be part myth. Furthermore, the Arabs would not get what they had fought for, as the ever imperialist states of Britain and France would divide the Middle East between themselves. This, after-all, was inadvertently why the whole war had begun.

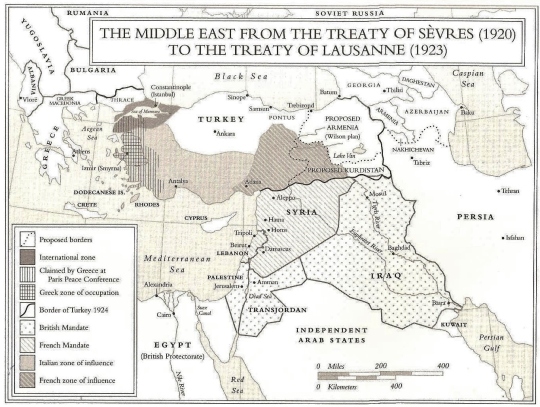

Lawrence’s companion, Prince Feisal, spoke to the delegation in the Paris Peace Conference while Lawrence translated. They must have looked an odd pair, especially the Englishman who had donned the white robes and gold sashing normally reserved for a senior sheik. Feisal said that the Arabs wanted self-determination, and while he was prepared to exempt Lebanon and Palestine from this demand, the rest of the Arab world should be given independence as the British and French had promised. When the French reminded Lawrence that their forces had fought in Syria during the crusades, Lawrence replied: “Yes, but the Crusaders had been defeated and the Crusades had failed.” Against the wishes of Lawrence and the Arabs, Britain was also determined to get a piece of the Middle East. Forced to prevent the non-colonial aspirations of the American President Woodrow Wilson by co-operating, the two imperial rivals came to a quick compromise; Britain would get Mesopotamia (Iraq) and Palestine, while France would get Syria and Lebanon. The Arabian Peninsula did not concern the imperial powers much, probably because all those ‘miles of sand’ were not of much value at the time.

The British motives were clear. For long they had supported the Ottoman Empire to keep the eastern end of the Mediterranean safe for their shipping, but now they needed an alternate hold in the area. This motivation highlights the geopolitical value of the area. Where once the Muslims had dominated the Silk Road which provided medieval Europe with eastern riches, now the British needed to protect its trade route to India. Of course, the Industrial Revolution had created new interests in the area’s oil, but the old geopolitical motives persisted as well.

Constantinople was promised to the Russian Czar at one point in the war, but the concessions made by the Bolsheviks cancelled that agreement. While the once-great Ottoman Empire was divided, Constantinople would remain in the hands of its owners since 1453. It was occupied by the allied powers (unofficially at first), but this would not survive the determination of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk. Remarking at the presence of allied warships in Constantinople’s harbour, he proclaimed: “As they have come, so they shall go.”

A modern Turkey would rise from the ashes

As a young officer in the Turkish military, Atatürk oversaw Austria’s annexation of Bosnia, and Bulgaria secession from Turkish influence. The Balkan wars of 1912 and 1913 result in the Ottomans loss of Albania and Macedonia, and Libya had been lost to the Italians. By 1914, the European portion of the Ottoman Empire, which had once stretched far into Hungary, was almost wholly gone – all that remained was an enclave in Thrace. Throughout the Great War, Atatürk remained the only undefeated Ottoman general. His reputation was made at Gallipoli, the same battle where many allied reputations were destroyed. In his eyes Turkey was defeated not by greater armies, but by greater civilization. Henceforth, he would ensure Turkey would adopt European-style culture and politics. Indeed, Turkey remains a secular state to this day.

Atatürk sent Inonu Ismet, a trusted general, to the Paris Peace Conference to negotiate. He was instructed to achieve an independent Turkey, and as a good soldier he intended to achieve just this by any means. Turkey’s new borders included almost all the Turkish speaking territories of their former Ottoman Empire, but the fact was the empire had ended and a new very different state had been birthed. It was truly the end of an age.

Works Cited

Anderson, Scott. Lawrence in Arabia. New York: Random House, 2013.

Kaplan, Robert D. The Revenge of Geography. New York: Random House, 2012.

MacMillan, Margaret. Paris 1919. New York: Random House, 2002.

‘Armed and Dangerous’ – China, America, and the North Korean Dilemma

North Korea is a state that has made it clear it does not intend to act according to international standards; it fulfills the definition of ‘rogue state’ perfectly. It also threatens the security of its neighbours. China, North Korea’s only ally, holds the key to resolving this dangerous situation. However China is caught in a precarious position. I argue that China and America can work through the North Korean dilemma together. To do this I present a past example of compromise.

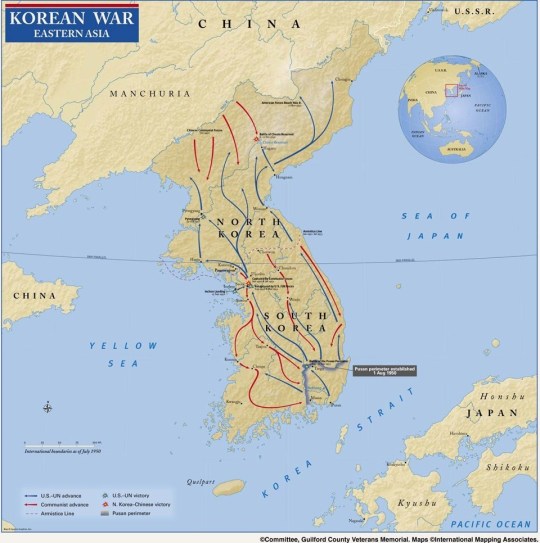

To understand the nature of the Kim dynasty and North Korea’s foreign policy today, one must first understand history. The United States and the Soviet Union divided Korea, a colonial possession of a defeated Japan, in 1945. North Korea fell into the Soviet sphere of influence, while Japan and South Korea would remain allied with the United States. In June of 1950 North Korea invaded South Korea. The world’s Cold War-era balance of power meant a civil war between communist and democratic factions would lead to foreign intervention. A UN sanctioned ‘police action’ meant a US led coalition would act to defend democratic South Korea.

To understand the nature of the Kim dynasty and North Korea’s foreign policy today, one must first understand history. The United States and the Soviet Union divided Korea, a colonial possession of a defeated Japan, in 1945. North Korea fell into the Soviet sphere of influence, while Japan and South Korea would remain allied with the United States. In June of 1950 North Korea invaded South Korea. The world’s Cold War-era balance of power meant a civil war between communist and democratic factions would lead to foreign intervention. A UN sanctioned ‘police action’ meant a US led coalition would act to defend democratic South Korea.

Initial North Korean victories meant United States and South Korean forces were pushed back to the Pusan Perimeter, on the southernmost tip of the peninsula. Meanwhile China acted to secure the Korean border, fearing the potential consequences of an American victory. During the Battle of the Pusan Perimeter, UN forces led by General Douglas MacArthur repelled the Korean People’s Army forces and turned the tide of the war. Subsequent campaigns saw US and South Korean forces push the Korean People’s Army forces past the 38th parallel: the North-South Korean border. When US forces neared the Chinese-Korean border, China intervened. Chinese and North Korean forces would push the United States back to the border area. Negotiations would bring about an armistice however the war would never officially end; the border between North and South Korea remains the world’s most heavily defended. To this day North Korea remains both allied to China and an enemy of South Korea and the United States.

All in the family

All in the family

Kim Il-sung ruled North Korea from 1948 – 1994, his son Kim Jong-il would secede him and his grandson Kim Jong-un embodies the dynastic chain today. The Jong-il and Jong-un governments have made provocative military actions a cornerstone of the regime’s foreign policy. In March of 2010 the North Korean navy is believed to have sunk the South Korean vessel Cheonan with a torpedo. In November North Korea shelled the South Korean border island of Yeonpyeong. North Korea’s 2006 and 2009 nuclear tests lead most to assume the nation possesses limited nuclear capabilities. However nuclear capabilities are not enough to threaten the security of neighbouring state, the Korean People’s army must possess a way of launching a nuclear warhead.

The security threat North Korea’s ‘space program’ presents

Even if North Korea were able to mount a nuclear weapon to one of its existing military rockets (a technology it has yet to master) its nuclear capabilities would only threaten South Korea and Japan. The only North Korean military rocket to have been successfully launched is its Nodong missile, an improved version of the Russian ‘scud’ chain of missiles. This missile’s range is limited, only South Korea, Japan, China, Russia, and Mongolia fall in its potential trajectory. Although China, Russia, and Mongolia all fall within this range, Pyongyang is not likely to attack these states. North Korea is still ‘at war’ with South Korea and the United States.

Although North Korea possesses military rockets with further range, it has yet to successfully test them as tests like these are extremely provocative. However last Wednesday North Korea launched a satellite into space. Not surprisingly mastering this feat and the feat of successfully launching an intercontinental ballistic missile with much further range than a Nodong missile takes transferable technology. After all, both techniques are considered rocket science. Therefore North Korea’s 12 December launch can be seen as a step in the direction of launching a missile at farther targets. The Unha-3 rocket that carried the regime’s satellite into space in effect extends the potential range in which existing Korean missiles reach. With further technological advances North Korea could threaten the United States‘ security, its enemy since 1950.

A call for action

There have been repeated rounds of sanctions and condemnation from the international community, however North Korea’s complete disregard for international peace warrants a stronger response. Should Kim Jong-un become further emboldened, the violence will surely escalate. It is likely Pyongyang will continue to push the limits. Past incidents of North Korean military aggression prove South Korea already faces major security threats. Therefore the time to act on North Korea is now, before the situation deteriorates further.

China’ precarious position

China hopes to gain great-power status in the international state system, but its ally in Pyongyang continues to put the region’s security in jeopardy. By being allied to a state that makes no attempt to abide by international norms China risks its legitimacy and thus its acceptance as a great-power in the region and the international community. Although China has expressed regret over North Korea’s nuclear testing and rocket launches, and the two regimes have often clashed, Beijing has yet to fully abandon its ally. This is because Beijing fears that should it attempt to forcefully influence North Korea, a spurned Kim Jong-un would lash out violently, provoking South Korea and subsequently America. A war against a Chinese ally on the Chinese border in which US forces are involved would be anathema to Beijing, it would mean China was losing influence in its region. A unified Korea would likely be an American ally, and could be used to check China’s rise. Thus China believes its only hope is that the situation remains as it appears today, it hopes for stability on the Korean Peninsula above all else.

The ticking time bomb

Although the above call for action is certainly warranted, the United States will not become involved militarily on the Korean Peninsula today because North Korea is China’s ally and falls in China’s sphere of influence. But should North Korea continue to act violently (a likely development) it could cause a war with America. This seems especially likely when one considers the North Korea’s satellite launch, as previously mentioned this is a step in the direction of endangering US security. The Pentagon constantly stations around 30,000 troops in both South Korea and Japan and as I argued in the Dragon’s Navy – Chinese Capabilities and American Policy, the United States must remain the dominant naval power in the Western Pacific. Therefore assuming the situation continues to grow more dangerous, the United States will eventually become involved. North Korea thus represents a ticking time bomb to Beijing.

The obvious question

What if China were to both act to remove Kim Jong-un from power and seek to maintain a strong relationship with a unified Korea? China already does more trade with South Korea, maybe it is time for China to force the two to unify. Perhaps America could agree Seoul’s new government would remain neutral, and would remove its troops from a unified Korea. China would likely agree to reunification on these terms.

Unfortunately there are many problems with this scenario. First of all, Chinese foreign policy rests on a doctrine of non-intervention. China has thus far not exported an ideology or colonized land, it would be simply hypocritical to start now. Secondly, America would want to ensure China was not simply throwing its weight around, it may act to either counter China’s aggression towards North Korea, or act vengefully after. Thirdly, even if China were to ‘ok’ its actions with Washington, the Pentagon would at the very least insist US Special Forces secured North Korea’s nuclear-program sites. As mentioned above, US forces acting within China’s sphere of influence would be seen as a foreign policy failure to Beijing.

But what if China and the United States could overcome their differences on North Korea? Perhaps Xi Jinping and Barack Obama could strike a deal wherein a mixture of covert and non-covert actions would see the Kim dynasty removed and Korea unified. There must be a compromise in which a conflict between the two is avoided while both save-face. The deal would have to specify that a unified Korea would remain neutral, and the US would likely have to withdraw its troops. Although 1950 saw war between Cold War rivals China and America, 1962 saw a compromise between the US and the USSR. John F. Kennedy worked out a secret deal with Nikita Khrushchev during the Cuban Missile Crisis. This deal saw both super-powers compromise. The USSR removed its missiles from Cuba while the US promised not to invade Cuba and removed its missiles from Turkey. To retain his image as a ‘cold warrior,’ the second part of Kennedy’s deal was kept secret. I argue the situation today can also be overcome, but China and America must first make some back-room deals similar to those made 50 years ago.

But what if China and the United States could overcome their differences on North Korea? Perhaps Xi Jinping and Barack Obama could strike a deal wherein a mixture of covert and non-covert actions would see the Kim dynasty removed and Korea unified. There must be a compromise in which a conflict between the two is avoided while both save-face. The deal would have to specify that a unified Korea would remain neutral, and the US would likely have to withdraw its troops. Although 1950 saw war between Cold War rivals China and America, 1962 saw a compromise between the US and the USSR. John F. Kennedy worked out a secret deal with Nikita Khrushchev during the Cuban Missile Crisis. This deal saw both super-powers compromise. The USSR removed its missiles from Cuba while the US promised not to invade Cuba and removed its missiles from Turkey. To retain his image as a ‘cold warrior,’ the second part of Kennedy’s deal was kept secret. I argue the situation today can also be overcome, but China and America must first make some back-room deals similar to those made 50 years ago.

Works Cited

“Active Duty Military Personnel Strengths by Regional Area and by Country (309A).” Department of Defense. 31 December 2009.

“Beaming.” The Economist, 15 December 2012.

http://www.economist.com/news/asia/21568386-kim-jong-uns-pyrotechnics- although-alarming-world-are-driven-chiefly-domestic

“Briefing by Defense Secretary Robert Gates and ROK Minister Lee.” America.gov Archive, 17 October 2008.

http://www.america.gov/st/texttrans- english/2008/October/20081020121847eaifas0.7119104.html

Brugion, Dino A. Eyeball to Eyeball. New York: Random House Inc., 1991.

Cha, Victor. “The Sinking of the Cheonan,” CSIS, 22 April 2010. http://csis.org/publication/sinking-cheonan

“Friends like these.” The Economist, 20 June 2011. http://www.economist.com/node/18897395

Kim, Jack and Mayumi Negishi. “North Korea rocket launch raises nuclear stakes.” Reuters, 12 December 2012.

http://www.reuters.com/article/2012/12/12/us-korea-north-rocket- idUSBRE8BB02K20121212

Mutton, Don and David A. Welch. the Cuban Missile Crisis a Concise History. New York: Oxford University Press, 2007.

Perlez, Jane. “Despite Risks, China Stays at North Korea’s Side to Keep U.S. at Bay.” The New York Times, 13 December 2012.

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/12/14/world/asia/china-stays-beside-north-korea-a- buffer-against-the-us.html?_r=0

“Guilford County Veterans Memoral Photo Panels.” Guilford NC Veterans Memorial and International Mapping Associates, 2010. http://www.gcveteransmemorial.org/photo-panels/

Vick, Charles P. “No-Dong-A.” GlobalSecurity.org, 2006.

http://www.globalsecurity.org/wmd/world/dprk/nd-1.htm

Vick, Charles P. “Taep’o-dong 2 (TD-2), NKSL-X-2.” GlobalSecurity.org, 1999.

http://www.globalsecurity.org/wmd/world/dprk/td-2.htm