Category: The Balance of Power

The New Great Game: America’s longest war

The United States of America has decided to endure its longest war. It has made this decision not because it believes it will prevail against a native insurgency – the United States has grander geopolitical interests in mind. By continuing to occupy Afghanistan, America is ensuring it is not overlooked in this century’s ‘New Great Game’.

Trump does not possess much interest in governing, he never has. On most of foreign policy, he has boasted of deferring decisions “to the generals”. While separating an ill-informed, uninterested, impulsive president from perilous decision-making is undoubtedly beneficial to the United States’ interests, it must be noted that the consequence is a markedly more imperialistic state with a renewed interest in realpolitik. This observation is clearest when considering the American administration’s decision to continue America’s longest war.

The geopolitical importance of Central Asia

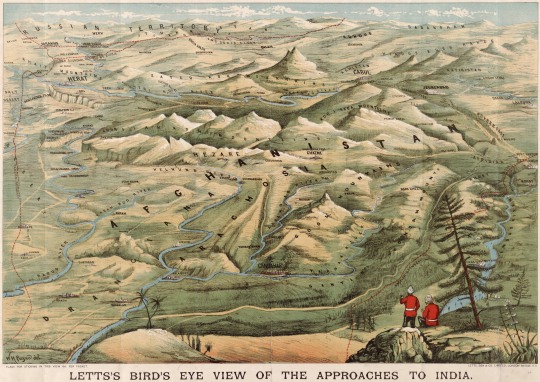

To India’s north, the Himalayas serve as a wall protecting India from foreign invasion. To the northeast, the Burmese jungles also present harsh enough conditions to shield India from advancing armies. It is from the northwest that India is most vulnerable. Here lies the Persian-Afghan plateau (a gradual incline rather than a divisive mountain range). It is from here that India has faced invading Greeks, Persians, and Mongols, because it is easier to march armies across a plain than over mountains or through jungle.

During the nineteenth century, the British Empire’s Indian holdings stood at the foot of the Persian-Afghan plateau. British officials, peering across this expanse, were concerned by an expanding Russian empire, fearing that Russian invaders would use the Afghan route to seize the crown jewel of the empire. Meanwhile, St Petersburg feared British commercial and military inroads into Central Asia. As such, Afghanistan was the key to security for each rival power – securing Afghanistan would counter each empire’s vulnerability. This rivalry was dubbed ‘the great game’.

The great game example illustrates a geopolitical reality of Eurasia: it is from Central Asia that all other Eurasian powers are most vulnerable. This reality was opined on by the geopolitical scholar Halford John Mackinder, who presented a paper titled ‘The Geographical Pivot of History’ to the Royal Geographical Society in 1904, and later published his book Democratic Ideals and Reality: A Study in the Politics of Reconstruction, which restated his ideas, in 1919. He summarizes his theory with overly quoted and simplistic maxim:

Who rules East Europe commands the Heartland [Central Asia]:

Who rules the Heartland [Central Asia] commands the World-Island [Eurasia]:

Who rules the World-Island [Eurasia] commands the World.

The first line of the maxim must be contextualized. Democratic Ideals and Reality was published during the Paris Peace Conference, and was meant to influence the statesmen at Versailles in their division of Europe after World War I – (the sub-title ‘A Study in the Politics of Reconstruction’ makes the book’s purpose clear). The Russian, Austrian, and Ottoman Empires had all collapsed, and Mackinder was making the case that it was a “vital necessity that there should be a tier of independent states between Germany and Russia”. This was a political goal rather than a geopolitical observation.

The second two lines are Mackinder’s maxim are more mechanical. Mackinder observed the world at a time when railways were opening Central Asia to trade, commerce, and conquest. Where once the area had been controlled exclusively by horse-riding nomads, it would soon be controlled by an industrialized power. Just as the Mongols had conquered all of Eurasia (and consequently terrorized medieval Europe) so too would Russia – and Mackinder was warning Britain and France that their navies would no longer allow them to command the World.

In one way, Mackinder’s maxim was proved right. After World War 2, Russia was able to project power globally because it controlled Central Asia, and most of Eurasia. Had it been preoccupied in Central Asia (for example, if it had to send armies to Siberia to counter Japan), Russia would have lost World War II. Instead, Russia could focus all its efforts on defeating, Germany, and in World War II’s aftermath, Russia asserted itself as one of the world’s great powers. By controlling Central Asia, Russia won World War II, and thereafter could project power as far away as Cuba.

On the other hand, Mackinder’s maxim was proved to be overreaching. Russia, even by controlling Central Asia, never commanded all of Eurasia, and never the World – it lost the Cold War. But it must be remembered that throughout the Cold War Russia remained vulnerable in Central Asia, China was often more of a rival than an ally, and in the Cold War’s final days Russia fought a prolonged War in Afghanistan. Moreover, I do not rely on Mackinder’s maxim as an empirical truth, rather it simply illustrates the geopolitical reality: it is from Central Asia that all other Eurasian powers are most vulnerable.

Modern geopolitics in Central Asia

The tectonic forces of geopolitics are reawakening in Central Asia. Where once the Soviet Union had dominated the region, new forces are asserting themselves: the rising powers of China and India, a Russia that hopes to claw back its Central Asian losses, and an invigorated Iran. China, in particular, deserves some further analysis.

Whereas Russia has always coveted access to the ocean, China is a similarly sized land power with a coastline in both the tropic and temperate zones. Therefore, according to Mackinder, China is theoretically in the world’s most geopolitically advantageous position, in that it can both control Central Asia and project power from Eurasia.

China is asserting itself in the former Soviet sphere of influence. It has become the leading trading partner for all the former Soviet republics (apart from Uzbekistan), as well as the region’s largest investor. Currently China is spearheading its “belt and road” initiative, in which China plans to invest billions of dollars in Central Asian infrastructure – ostensibly to project economic power.

The American Top Brass’s realpolitik

The result of all this is clear. The balance of power in Central Asia is changing. China is asserting itself. Russia is vulnerable. Iran (who no longer has the regional rival Iraq to worry about) is projecting power as far away as Syria and Yemen – it could just as easily turn east. Whichever power controls Central Asia (in the end, most likely China), can then control Eurasia.

Serendipitously, it is at this time that America finds itself with an outpost right in the heart of Central Asia: Afghanistan. Why would America squander the opportunity to have its thumb on the scale during this ‘new great game’? Another president may have overridden his (or her) generals’ focus on the geopolitical forces in favour of domestic or even global humanitarianism, but this president is happy to cede such decisions to the military. The result is a renewed realism. Security is paramount. Any opportunity to influence the dynamic forces of Central Asian geopolitics must be seized because he who rules the Heartland commands the World-Island, and he who rules the World-Island commands the World.

Works Cited

The Economist, What is China’s belt and road initiative? https://www.economist.com/blogs/economist-explains/2017/05/economist-explains-11

The Economist, Xi Jinping and Vladimir Putin behave like the best of buddies, https://www.economist.com/news/china/21725611-suspicion-between-russia-and-china-runs-deep-xi-jinping-and-vladimir-putin-behave-best

Kaplan, Robert D., The Revenge of Geography. New York: Random House, 2012.

Mackinder, Sir Halford J., Democratic Ideals and Reality: A Study in the Politics of Reconstruction. Washington D.C.: National Defense University Press, 1942.

The West’s Decline: A Desperate Call for Action

In 2012, I named my fledgling blog The State of the Century. Never have I been more pessimistic about the state of the 21st century.

All empires fall. One day, the West too will be a faded memory, to be idealized by those attempting to emulate its affluence, just as the Holy Roman Empire was meant to be the rebirth of its namesake. But never would I have imagined the cause of the West’s decline to be so insidious: a cancer that rots its founding pillars. I intend to trace the growth of this cancer, and present a desperate call for rationalism to prevail.

The West is a haven of peace and prosperity. Western Europe, the United States, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Japan and South Korea (which I will collectively refer to as ‘the West’) is home to more than a billion people. Imagine for a second, Norway and Sweden going to war, or Japan collapsing into civil war, or Australia annexing New Zealand, these scenarios currently remain preposterous. In this region people do not starve and they are not slaughtered. Never in humanity’s history have more people enjoyed a higher quality of life.

As such, I greatly fear the collapse of the Western world order. Everyone who lives within its borders must as well; anyone who doesn’t is not self-interested. Even those living on its periphery should fear the West’s fall – a rising tide raises all ships, and a drowning swimmer is liable to drag others down. There are those who exploit the corruption and authoritarianism of the periphery for their personal advantage (Vladimir Putin is an example), who would greatly benefit from the West’s fall. But the periphery’s masses should, and generally do, want to join the West or benefit from the prosperity it enjoys.

The phenomenon of the West, and the prosperity it brings, was made possible by many competing forces, but none more important than the rule of law. All other causational forces (democracy, technology, the free market etc.) can be traced back to the rule of law. Democracy would not function if it were not for a respect for the rules. Technology could not flourish if it were not for the scientific method (in itself a set of laws; evidence must trump prejudice). The free market could not function if contractual obligations were ignored by the wealthy and powerful.

If a future civilization is lucky enough to experience institutional learning, its textbooks will trace the West’s decline back to the first year of the 21st century, 2001. It was then that a ragtag suicide cult flew a few planes into a few buildings. This group hated the West, and sought its destruction. Their ringleader hatched a plan that in hindsight can only be called brilliant (evil yes, but brilliant). Osama Bin Laden was an extreme xenophobe. In his mind, his nation (people who share his cultural and religious identity) must conquer all others. But how does a small group of guerilla fighters overcome an empire?

Terrorism, as warfare, does not seek victory on the battlefield. It seeks to disrupt and ultimately disintegrate the enemy. It is meant to cause enemy forces to overreact, to be cast as brutal oppressors, and to sap the enemy nation of its will to fight.

The West’s reaction to 9/11 can only be described as an overreaction. The Bush administration possessed an inflated sense of the nation’s capacity for war. The group that occupied Washington’s halls of power on September the 11th, 2001, could not remember defeat at the hands of an enemy. The Cold War, Desert Storm, and the Balkan Wars had all been won. What does a warrior nation do when it has no one left to fight? With the national fervour still high, and early Afghan victories ripe in the national consciousness, the Bush administration turned on a familiar enemy, but one that had no connection whatsoever to the terrorists it sought to bring to justice.

Predictably, no tangible benefit was brought to the citizens West in the West’s response to 9/11, and as the years ground on the West lost the plot, and with it legitimacy. It ceased to be the prosperous haven of humanity’s collective imagination; it became to many a tyrant reigning over the world order.

Although the narrative of the West’s decline begins on September 11th, 2001, it is a mistake to attach too great an agency to 9/11 and its aftermath. Globalisation, itself caused by the rise of the Western world order, has presented a challenge the West has yet to overcome, rising inequality. Inequality is a fundamental challenge to the Western world order because it erodes the ideal the West was founded upon: the rule of law. If the system works to advance the position of the powerful to the detriment of the weak, the perception is that all are not equal before the law. When no obvious answer to this new challenge presented itself, the Western masses became restless, angry, and eager to lash out.

The challenge globalisation presents exists independent of 9/11. But 9/11 created the climate in which the anger caused by globalisation developed. More than a decade after 9/11, the narrative had turned against the West. The Western political establishment was now at best incompetent in its response to the terrorist threat, at worst it was seen as corrupt and colonial. At the same time, there were those that were inspired by Osama Bin Laden’s brazen rebellion to the Western world order. The Arab Spring brought about failed revolutions, failed states, misery, suffering, and mass migration. It also presented a gaping wound for a group of disenfranchised radicals to infect. Globalisation allowed Western citizens (themselves disenfranchised by the West) to join the infection of ISIS – a cruel twist in the story of the West’s decline. But worst of all, ISIS presented a new narrative to the citizens of the West.

A decade and a half after 9/11, it becomes necessary to recap the interrelated forces that are contributing to the West’s decline. First, the existing political establishment is seen as incompetent and corrupt. Rising inequality is eroding the hope the Western order inspires. The Western masses are angered. A villainous insurgency persists on the West’s periphery, itself a regrown head of the hydra that the West had initially sought to slay. Technological advances work to spread the hydra’s xenophobic message. And, no easy answers present themselves.

With no easy answers, the collective Western imagination is tempted by the memory of the golden decade the West enjoyed at the end of the 20th century. What had changed between then and now? The world then had been less globalised and connected. It is easy for the collective imagination to become enthralled by the belief that global connectivity is itself the route of problem. This belief is particularly attractive because it is not entirely untrue; however raising walls will not work to advance the position of the Western world order.

When the Western masses are fed a daily stream of reports of peripheral terrorists thwarting Western responses, and when these terrorists flaunt a message of national superiority (ie. “our nation is superior”), it is easy for the Western masses to respond with an equally xenophobic message (ie. “no, our nation is superior ”). With mass migration brought about by both globalisation and the Arab Spring, it is easy for a small group of nationalist bigots to inspire a perception that barbarian hordes are at the Western gates.

When times are desperate, when the existence of the nation is threatened by barbarian hordes, the rule of law becomes secondary to security. Efficiency becomes all important. It becomes necessary to center power upon a few who can focus the nation’s efforts against its perceived enemy. When the ends justify these means, patriotism becomes fascism. In America, this new fascist trend has been embodied by an ill-qualified narcissist (as fascist trends often are).

Not all nationalism is fascism. The support you hold for your country’s World Cup team is nationalism, but not fascism. Fascism is when an authoritarian government derives legitimacy from ultra-nationalist sentiments. The rise of fascism is the advancement of nationalist government policies, the correlated vilification of other nations both foreign and domestic, and general erosion of the rule of law as power is centered upon a single authority. With its demonization of outsiders and opposition alike, and disrespect for the judicial branch of government, it is difficult to describe the political trend that the West is currently experiencing as a desire for anything but fascism (even if the authoritarian aspect has not been achieved quite yet).

It is the rule of law that makes the Western world order what it is, and it is the rule of law that is most compromised by the rise of Western ‘strongmen’ who spout false hope and exploit the trumped-up national fear of being overrun by ‘barbarians’. Those who present a reasoned and nuanced solution, wherein globalisation itself works to spread the rule of law through greater connectivity, fail to inspire those in search of an easy answer. Technological advances combined with the Western ideal of freedom of speech (itself a necessary component of the rule of law) work to drown out the complicated in favour of the simple.

And so the rise of Western fascism becomes a vicious cycle. Easy answers and misinformation spread like contagion through globalised communications technology. The truth becomes murky. Facts can be debased and dismissed as mere opinion. Conspiracy theories can be paraded as legitimate debate. Then, when our constitutional foundations are breached, how can we hope to reverse the decline? How can we hope to counter the onslaught of fascist ends-justify-the-means rhetoric? The problem is endemic, insidious, and a cancer that rots the institutions that make the Western world a haven of prosperity.

It is truly unfortunate that at this time in history, when the West is most divided by false hope and hatred, the most perilous problem humanity has ever faced has presented itself: climate change. The western world is addicted to a fuel that provides prosperity but undermines our planet’s terrain. As such, it deserves the Western world’s entire focus. But climate change is a problem that cannot be personified upon an enemy. Thus, the solution is anything but easy, and the masses have already become drunk on simple sentiments and xenophobic lies spun by ‘strongmen’ who have been and are being swept to power around the Western world. It is now that the West can least afford complacency.

I find little on which to base optimism for the state of the Western world order. The solution is not easy. It lays (as I have alluded) in a reasoned and nuanced approach, the scope of which I do not attempt to describe. Terrorism is a distraction. Misinformation is the problem. Reason and rationality must triumph, or else the West will fall. But when half-truths can be elevated to doctrine by neo-fascist Western leaders, I have little hope for reason.

I call those who share my affection for rationality to remain vigilant. Do not be complacent when you hear an opinion that advances the insidious spread of Western fascism. Stand up and be counted. If nothing else you will be remembered as being on the right side of history, as it is presented by the textbooks of some future civilization that lays on the far side of the dark-age humanity currently stares in the face.

The Eclipse of the Ottoman Empire – The End of a Medieval Reality

Many see the First World War as the end of the Prussian monarchy, or the birth of Communist Russia, but overlook the eclipse of one of the world’s greatest empires, that of the Ottomans. Since the defeat of Christian Byzantium at the sack of Constantinople, Europe’s south-eastern flank would be dominated by the world of Islam. This reality – born in the middle-ages – would persist until 1918. The First World War marked the end of an age and the beginning of another in many respects, but perhaps the defeat of the Ottoman Empire is the most drastic example of this historic watershed.

While Europe was trapped in centuries of dark ages, the world of Islam had been culturally and technologically ahead. Muslim cities in the medieval period possessed advanced infrastructure and architecture, the accomplishments of their universities and libraries meant they were the world’s best in many areas of science and industry. Once North Africa and much of the Middle East had belonged to the Romans, but by the Medieval period these lands had fallen to the Caliphate. Byzantium was the Medieval continuation of the Eastern Roman Empire. The Western Roman Empire had been overrun by barbarian hordes, its title reused by the first Holy Roman Emperor, the Frankish King Charlemagne. To medieval Europe, the Muslim threat was embodied by the Ottoman Turks, a reality which continued into the Renaissance and the Age of Discovery, and indeed until the Great War. The Turks were the face of Islam from the defeat of the Byzantines at Battle of Manzikert in 1071 until 1918; only recently have the Arabs been recognised as the head of Muslim civilization.

Constantinople had at one point been the greatest city in Europe. It had been the capital of Byzantium, which had remained a Christian entity since the Eastern Roman Emperor Constantine ruled from its seat. But the city fell to the Turks in 1453. If this caused anxiety for the Christian monarchs of eastern and southern Europe, the next century would cause considerably more.

Following Turkish conquest of Damascus in 1516 and their subsequent advances on Egypt and Arabia, the janissary armies of the Ottomans turned on Hungary, which had become the great eastern christian bastion after the fall of Constantinople. Following the Battle of Mohacs in 1526, Hungary was overrun. The Ottoman Empire was now at its height, and covered more territory than that of Rome. One could hardly blame scholars at the time for concluding that the future would belong to the Islamic world, and much of the continent would inevitably belong to the Sultan. This inclination nearly became reality when the Ottomans besieged Vienna in 1529, and when they did so again in 1683.

The capitulation of the Ottomans: a drawn-out affair

Yet the Ottoman Empire would inevitably falter and collapse. Its armies and navies, however formidable, were overextended – needing to maintain frontiers in Central Europe, the Crimean, the Mediterranean, the Red Sea, and the Near East where the Ottomans were challenged by the Persians. This geographic challenge of the area is one I explore further in The Geopolitical Realities of Eurasia. Its challenges were not insurmountable, but as a single entity the Ottoman Empire was overly centralised. Whereas European division was in many ways the continent’s strength, as competing states would challenge one-another to explore and expand, one foolish Sultan could do more damage to the Ottoman Empire that any lone European monarch or pope could ever hope to accomplish. From 1566 on, there reigned thirteen incompetent sultans in succession, sealing the empire’s doom.

It was the slow retreat of the Turks that caused the European powers to look towards the Balkans and consider who would benefit from the Turkish collapse. It was this power struggle, known as the ‘Eastern Question,’ that among other things motivated a Habsburg Archduke to parade himself and his nation’s power in Sarajevo, whose death in turn triggered the Great War that would divide the lands that still remained under Turkish control.

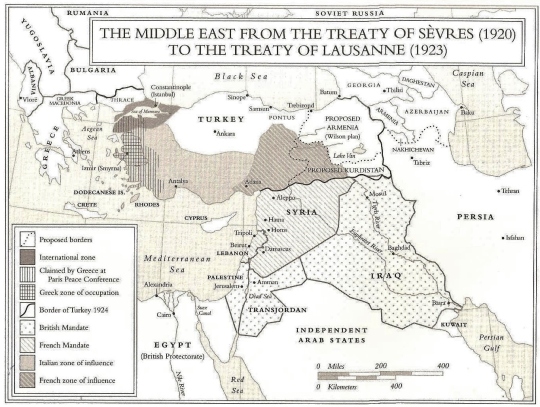

The First World War severed the Arab provinces from the sultan’s grip. Ironically, early twentieth-century Arabian warfare was remarkably similar to that of fourteenth-century Europe, allowing the medieval-military historian Thomas Edward Lawrence to exploit the Arabic advantages. Of course, this legendary figure did not engineer the Arabic revolt on his own, his own account of the events in The Seven Pillars of Wisdom, was admitted to be part myth. Furthermore, the Arabs would not get what they had fought for, as the ever imperialist states of Britain and France would divide the Middle East between themselves. This, after-all, was inadvertently why the whole war had begun.

Lawrence’s companion, Prince Feisal, spoke to the delegation in the Paris Peace Conference while Lawrence translated. They must have looked an odd pair, especially the Englishman who had donned the white robes and gold sashing normally reserved for a senior sheik. Feisal said that the Arabs wanted self-determination, and while he was prepared to exempt Lebanon and Palestine from this demand, the rest of the Arab world should be given independence as the British and French had promised. When the French reminded Lawrence that their forces had fought in Syria during the crusades, Lawrence replied: “Yes, but the Crusaders had been defeated and the Crusades had failed.” Against the wishes of Lawrence and the Arabs, Britain was also determined to get a piece of the Middle East. Forced to prevent the non-colonial aspirations of the American President Woodrow Wilson by co-operating, the two imperial rivals came to a quick compromise; Britain would get Mesopotamia (Iraq) and Palestine, while France would get Syria and Lebanon. The Arabian Peninsula did not concern the imperial powers much, probably because all those ‘miles of sand’ were not of much value at the time.

The British motives were clear. For long they had supported the Ottoman Empire to keep the eastern end of the Mediterranean safe for their shipping, but now they needed an alternate hold in the area. This motivation highlights the geopolitical value of the area. Where once the Muslims had dominated the Silk Road which provided medieval Europe with eastern riches, now the British needed to protect its trade route to India. Of course, the Industrial Revolution had created new interests in the area’s oil, but the old geopolitical motives persisted as well.

Constantinople was promised to the Russian Czar at one point in the war, but the concessions made by the Bolsheviks cancelled that agreement. While the once-great Ottoman Empire was divided, Constantinople would remain in the hands of its owners since 1453. It was occupied by the allied powers (unofficially at first), but this would not survive the determination of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk. Remarking at the presence of allied warships in Constantinople’s harbour, he proclaimed: “As they have come, so they shall go.”

A modern Turkey would rise from the ashes

As a young officer in the Turkish military, Atatürk oversaw Austria’s annexation of Bosnia, and Bulgaria secession from Turkish influence. The Balkan wars of 1912 and 1913 result in the Ottomans loss of Albania and Macedonia, and Libya had been lost to the Italians. By 1914, the European portion of the Ottoman Empire, which had once stretched far into Hungary, was almost wholly gone – all that remained was an enclave in Thrace. Throughout the Great War, Atatürk remained the only undefeated Ottoman general. His reputation was made at Gallipoli, the same battle where many allied reputations were destroyed. In his eyes Turkey was defeated not by greater armies, but by greater civilization. Henceforth, he would ensure Turkey would adopt European-style culture and politics. Indeed, Turkey remains a secular state to this day.

Atatürk sent Inonu Ismet, a trusted general, to the Paris Peace Conference to negotiate. He was instructed to achieve an independent Turkey, and as a good soldier he intended to achieve just this by any means. Turkey’s new borders included almost all the Turkish speaking territories of their former Ottoman Empire, but the fact was the empire had ended and a new very different state had been birthed. It was truly the end of an age.

Works Cited

Anderson, Scott. Lawrence in Arabia. New York: Random House, 2013.

Kaplan, Robert D. The Revenge of Geography. New York: Random House, 2012.

MacMillan, Margaret. Paris 1919. New York: Random House, 2002.