Category: Europe

The Cornered Bear – Russia’s Foreign Policy Paradigm

Understanding the Kremlin’s new found aggression towards Ukraine requires an understanding of Russia’s history, and President Vladimir Putin’s foreign-policy motif. An understanding is essential in avoiding the frigid hostility of the Cold War.

In 2008, Russia invaded Georgia. The world turned a blind eye, partly because Georgia is an insignificant state on the fringe of Europe but mostly because the costs of cutting Russia adrift would be too high. Days after the Sochi Olympics, Russia annexed Crimea. The world accepted it because Crimea should have been Russian all along – the territory had been transferred to Ukraine by Khrushchev in 1954. If the Soviet leader were alive today he would likely admit that in hindsight the transfer was a mistake. Now the Russian army is infiltrated eastern Ukraine, albeit subversively. Putin denies any such action, however this is highly implausible. The attacks were co-ordinated, and in strategically useful places that had seen few prior protests. Ukraine is a part of Europe, it was moving towards EU membership, and despite Moscow’s perception it is a sovereign state. Disregarding minor sanctions, why is the West standing by while Russia destabilises its neighbour? The answer is that ultimately, Ukraine remains within Russia’s sphere of influence and the land matters more to Putin than it does to any Western leader. Those two reasons are what the whole conflict is over, after all.

Its all about geography – the vast Russian landmass and its foreign policy

The Russian foreign-policy paradigm is one I have examined many times; recent events make the explanation relevant once again. The Russian landmass is incredibly large, flat, and thus vulnerable. Throughout history, the peoples that populated this landmass secured their frontiers aggressively. This is true of the Scythians, the Huns, the Mongols, the Russian Empire of the Czars, the Soviets, and the modern Russian Federation. Throughout Russia’s history, it has acted as “a land power that had to keep attacking and exploring in all directions or itself be vanquished.” We see this in the 1800s when Russia pushed into Eastern Europe in an attempt to block France, and again in 1945 when Moscow used Eastern Europe as a buffer-zone against a resurgent Germany. Russia has also pushed into Afghanistan to block the British during the Great Game, and conquered the Far East to block China. These same motives were at play when the Soviets invaded Afghanistan in 1979. Moscow again felt vulnerable when the Soviet Union dissolved and it lost the buffer-zone it gained in 1945.

Today Russia is the most vulnerable it has been in centuries

During the collapse of the Soviet Union, Moscow gave up much of its influence of both the Warsaw Pact and the former Soviet Republic states. Many of these states subsequently joined the EU and NATO. This left Russia even smaller, and in Moscow’s eyes even more vulnerable as a result than it was in the aftermath of the First World War, when it was bitterly defeated by the Central Powers. Indeed, Russia holds a similar amount of territory today as it did under Peter the Great.

Expanding EU integration is seen by Moscow as an attempt to install Russia-hostile political regimes in Russia’s former sphere of influence. In contrast to the EU’s value-driven foreign policy, Russia’s government places importance on stable governance, it believes the promotion of democracy and the rule of law risks regional stability. Thus, Moscow remains very wary of the EU’s Eastern Partnership, an attempt to deepen EU ties with the post-Soviet republics of Ukraine, Belarus, Moldova, Georgia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan. To Moscow this is an attempt by the EU to contain Russia by removing the legitimate authoritarian regimes and installing Russia-hostile governments. This is why today Putin believes the European Union is a threat, and why the Ukraine is of utmost importance. If the country were to slip out of Moscow’s sphere of influence, Russia would be left that much more vulnerable. The nation feels cornered.

The man with the plan

Putin has stated that “the demise of the Soviet Union was the greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the century.” He sees the world as in a state of transition from an American dominated power balance that began with the fall of the USSR to one that is made up of several global powers. As such the Russian President’s goal is to re-establish Russia as a great-power, if not in a bipolar state system than in a multipolar state system. Allowing Ukraine to drift westwards is in direct conflict with this goal, and thus the overthrow of Russian-backed President Viktor Yanukovych in favour of a European oriented interim government is anathema to the Kremlin. The Ukraine is in particular a more personal-desire to the Russian national narrative, as it was in Kiev that the modern Russian state was born. Furthermore the country borders Russia, cutting deep into its southern flank. To the Kremlin, a western-oriented Ukraine is likely even more undesirable than a western-oriented Poland.

So what does Putin hope to achieve in the Ukraine? It is unlikely that the intention is to annex Ukraine’s east, occupation would come at heavy costs, both politically and militarily. It is more likely that the Kremlin hopes to incite civil conflict to erode the authority of the new pro-Western government in Kiev. In Putin’s eyes, a destabilised Ukraine is better than a Western one.

The West’s Balancing Act

With this in mind, how best can the West counter Russia’s new found aggression? Both sanctions and NATO military exercises are certainly necessary, the latter to assure the Baltic states that they are not second-class NATO members, and can count on NATO to come to their defense. However, the West must be very careful not to overact, thereby plunging the world back into a Cold War, or worse. A complete isolation of Russia would be devastating to Europe’s economy, a distraction to America’s “Asian Pivot,” and destructive to overall global security. A cornered bear is a dangerous one, and West must understand where it can act, and what is outside of its own sphere of influence. Henry Kissinger eloquently described the balancing act the West must achieve in order to counter Moscow without ostracising it, and it all comes down to understanding Putin’s motives.

“Paradoxically, a Russia is a country that has enormous internal problems … but it is in a piece of strategic real estate from St Petersburg to Moscow. It is in everybody’s interest that it becomes part of the international system, and not an isolated island. One has to interpret Putin not like a Hitler-type, as he has been, but as a Russian Czar who is trying to achieve the maximum for his country. We are correct in standing up to him, but we also have to know when the confrontation should end.”

Works Cited

Bugajski, Janusz. Expanding Eurasia: Russia’s European Ambitions. Washington D.C.: The Center for Strategic and International Studies Press, 2008.

Insatiable, The Economist, 19 April 2014.

Kaplan, Robert D. The Revenge of Geography. New York: Random House, 2012.

Kissinger, Henry. GPS, 11 May 2014.

Light, Margot. “Russia and Europe and the process of EU enlargement.” In The Multilateral Dimension in Russian Foreign Policy, edited by Elana Wilson Rowe and Stina Torjesen, 83-96. New York: Routledge, 2009.

Lucas, Edward. The New Cold War: Putin’s Russia and the Threat to the West. New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2009).

Mankoff, Jeffrey. Russian Foreign Policy: The Return of Great Power Politics. Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield, 2012.

Zagorski, Andrei. “The limits of a global consensus on security: the case of Russia.” Global Security in a Multipolar World (2009): 67-84. Accessed March 6, 2012.http://www.iss.europa.eu/uploads/media/cp118.pdf

Conflicts Converge on Sochi’s Olympics

The 2014 Winter Olympic Games will showcase the Russian state, but not for the reasons for which Russia was granted the honour of hosting the Olympics. Sports fans will enjoy watching the endless coverage that comes with the spectacle. So too will those who adore foreign policy.

The Sochi Winter Olympic Games will be the first held in Russia since the breakup of the USSR – the last being the Moscow Olympics of 1980. As such this will be Putin’s opportunity to showcase his new(ish) Russia to the world. And showcase he will. As of October 2013, the budget had already exceeded $50billion, which dwarfs London’s budget of $19billion, and even Beijing’s which cost $40billion.

Unbeknownst to the committee that granted Sochi the games in 2007, back when Russia appeared to be a reforming nation with a promising ‘BRIC’ status economy, the event will be a geopolitical spectacle as well as one of sport. A number of conflicts are converging upon the Black Sea resort city of Sochi. I will examine each in turn.

Russia’s Homophobic Legislation

Modern Western values are at conflict with traditional Russian ones. The Kremlin has passed a law banning “pro-homosexual propaganda.” This has created a climate of aggression, in which vigilantes attack sexual minorities. Vladimir Putin’s purpose for the act is simple. It came as a surprise to the populist Putin to face active protests from the liberal middle class centered mainly in Moscow and St. Petersburg. However the Russian majority remains solidly homophobic, as much of the West did until quite recently. The new anti-gay legislation achieves two things. First the law is meant to drive a cultural wedge between the liberal opposition to Putin and his remaining supporters in the more conservative provinces. Second it differentiates Putin from the West, making the West appear alien and immoral to the traditional Russian public, and making Putin the apparent protector of Russian values.

Many advocated for a boycott of the Russian games in response to this discriminatory legislation, but none came. However I would argue the alternative will achieve more for gay-rights. Soon, thousands of athletes and fans from around the world will cluster in Sochi, and inevitably many of these individuals will be gay or supporters of the marginalised gay community in Russia. It would not surprise me to see rainbow flags in the stands, or perhaps even more ostentatious forms of protest. If this is done by foreigners in Sochi, there is nothing the Russian authorities can do. If it is done by Russians in greater Russia, the whole world will be watching the Kremlin’s reaction.

Unrest in the Ukraine

On December 17th of last year, an agreement was reached between Putin and Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych whereby Russia would lend Ukraine $15billion and would slash the gas price from $400 to $268 per thousand cubic metres. This was all a result of Yanukovych’s ditching of an association agreement with the EU.

Ukrainians have poured into the streets in response, besieging government buildings and generally causing unrest. Many must feel their country slowly slipping back behind the Soviet veil. This of course is Putin’s strategy. Russia’s foreign policy paradigm is traceable to the thirteenth century. To maintain its security, Russia must conquer as much territory as it can. Russia was left extremely vulnerable when the Soviet Union dissolved, more vulnerable even than it was left in the wake of the First World War, when it was bitterly defeated by the central powers. Ukraine is of a more personal desire to the Kremlin, because it was in Kiev that the modern Russian state was born. Putin continues to see the world in traditional, realist terms, and he wishes to bring Russia back to great-power status.

Sochi is literally less than a day’s drive from Kiev, and soon Ukrainian athletes and fans will be flocking to the Black Sea resort city. Since their own country’s political crisis is intimately tied to the Russian state, one can expect there to be some animosity between the two camps. However, let us not forget the anti-Putin protests that occurred not so long ago. Perhaps Ukrainian activism will spark something similar in Russia.

Russia’s Support of the Syrian Regime

For nearly three years civil war has raged in Syria. The regime of Bashar al-Assad has brutally supressed its own population, stooping so low as to gas Syrian civilians with nerve agents. If that did anything to attract world attention to the crisis, the recent report of three former war crimes prosecutors – saying they have seen compelling evidence of the systematic murder of some 11,000 detainees through starvation, beatings and torture – will only do more. The evidence of the war crimes is hard to fault. A former photographer for the Syrian regime defected. The report’s authors, who interviewed the source for three days, served as prosecutors at the criminal tribunals of the former Yugoslavia.

Despite the growing disgust the international community has for Assad, Russia has remained steadfastly in support of one of its last allies in the region. Moscow has continued to supply Assad’s army with military equipment. Russia possesses a Mediterranean naval-port in Tartous; it could lose this strategically vital military base should the Assad regime fall. But beyond this specific attachment to Syria, one must again recall Russia’s entire foreign-policy motif. It sees the middle-east as its ‘soft underbelly,’ much like United States sees Central America as its ‘backyard.’ To lose an ally in the geopolitically important region of the Middle East would be anathema to the Kremlin.

Soon, all eyes will be on Russia. If anything happens to make Syria of extreme interest during the fortnight that is the Olympic Games, questions will be asked, and Putin will have to explain Russia’s steadfast support of a madman. If nothing happens, questions will still be asked.

The Syrian conflict also exemplifies a broader struggle between Moscow and Washington. This relationship has deteriorated in recent years with Russian acts such as the amnesty granted to Edward Snowden, and American acts such as Obama’s cancellation of a September summit. The two states were most at-odds while during the period in September when America nearly engaged in an armed response to Assad’s use of chemical weapons. By engineering a face-saving alternative, Putin emerged from this struggle the apparent victor. The Olympics will allow Putin an opportunity to cement this posturing success.

Terrorism in the Caucasus

Probably the most troubling concern surrounding Sochi is that of the terrorists in the Caucasus region itself. Regions such as Dagestan are highly volatile, rebels there were responsible for the December Volgograd bombings. No doubt this is one of the two central reasons why the games are of such high-cost, the other being corruption. All aspects of the Russian military have been mobilised to prevent such threats – including submarines to patrol the Black Sea. If even a minor event occurs to marginalise security of the games, all eyes will be on Putin, and the Russian response. It is highly likely an attack will occur somewhere, even though Sochi itself has become a veritable stronghold. Russian authorities are known for their ruthlessness when dealing with domestic threats. If human-rights and other Western values are sidestepped, the world will witness it.

Showcasing Russian Authoritarianism

Many hoped Russia would liberalise after 1991. Putin has quashed these hopes. His return to the presidency through a rigged election displays the sham that was Dimitri Medvedev’s presidential reign. The country has returned to its Soviet ideals, or perhaps closer to its Czarist ones. To the extent that the Olympics will be a stage for Putin to dabble in his usual populist stunts, these games remind one of the triumphs of Rome: an opportunity for one man to centralise political power on himself alone. This, of course, is eerily similar to the strategy of Stalin.

Works Cited

Freedland, Jonathan. “Can evidence of mass killings in Syria end the inertia? Only with Putin’s help.” The Guardian, 2014.

Kaplan, Robert D. The Revenge of Geography. New York: Random House, 2012.

“Most expensive Olympics in history.” RT, February 2013. http://rt.com/business/sochi-cost-record-history-404/

“Putin’s Expensive Victory.” The Economist, 31 December 2013.

Treisman, Daniel. “The Wrong Way to Punish Putin.” Foreign Affairs, August 2013.

The Eclipse of the Ottoman Empire – The End of a Medieval Reality

Many see the First World War as the end of the Prussian monarchy, or the birth of Communist Russia, but overlook the eclipse of one of the world’s greatest empires, that of the Ottomans. Since the defeat of Christian Byzantium at the sack of Constantinople, Europe’s south-eastern flank would be dominated by the world of Islam. This reality – born in the middle-ages – would persist until 1918. The First World War marked the end of an age and the beginning of another in many respects, but perhaps the defeat of the Ottoman Empire is the most drastic example of this historic watershed.

While Europe was trapped in centuries of dark ages, the world of Islam had been culturally and technologically ahead. Muslim cities in the medieval period possessed advanced infrastructure and architecture, the accomplishments of their universities and libraries meant they were the world’s best in many areas of science and industry. Once North Africa and much of the Middle East had belonged to the Romans, but by the Medieval period these lands had fallen to the Caliphate. Byzantium was the Medieval continuation of the Eastern Roman Empire. The Western Roman Empire had been overrun by barbarian hordes, its title reused by the first Holy Roman Emperor, the Frankish King Charlemagne. To medieval Europe, the Muslim threat was embodied by the Ottoman Turks, a reality which continued into the Renaissance and the Age of Discovery, and indeed until the Great War. The Turks were the face of Islam from the defeat of the Byzantines at Battle of Manzikert in 1071 until 1918; only recently have the Arabs been recognised as the head of Muslim civilization.

Constantinople had at one point been the greatest city in Europe. It had been the capital of Byzantium, which had remained a Christian entity since the Eastern Roman Emperor Constantine ruled from its seat. But the city fell to the Turks in 1453. If this caused anxiety for the Christian monarchs of eastern and southern Europe, the next century would cause considerably more.

Following Turkish conquest of Damascus in 1516 and their subsequent advances on Egypt and Arabia, the janissary armies of the Ottomans turned on Hungary, which had become the great eastern christian bastion after the fall of Constantinople. Following the Battle of Mohacs in 1526, Hungary was overrun. The Ottoman Empire was now at its height, and covered more territory than that of Rome. One could hardly blame scholars at the time for concluding that the future would belong to the Islamic world, and much of the continent would inevitably belong to the Sultan. This inclination nearly became reality when the Ottomans besieged Vienna in 1529, and when they did so again in 1683.

The capitulation of the Ottomans: a drawn-out affair

Yet the Ottoman Empire would inevitably falter and collapse. Its armies and navies, however formidable, were overextended – needing to maintain frontiers in Central Europe, the Crimean, the Mediterranean, the Red Sea, and the Near East where the Ottomans were challenged by the Persians. This geographic challenge of the area is one I explore further in The Geopolitical Realities of Eurasia. Its challenges were not insurmountable, but as a single entity the Ottoman Empire was overly centralised. Whereas European division was in many ways the continent’s strength, as competing states would challenge one-another to explore and expand, one foolish Sultan could do more damage to the Ottoman Empire that any lone European monarch or pope could ever hope to accomplish. From 1566 on, there reigned thirteen incompetent sultans in succession, sealing the empire’s doom.

It was the slow retreat of the Turks that caused the European powers to look towards the Balkans and consider who would benefit from the Turkish collapse. It was this power struggle, known as the ‘Eastern Question,’ that among other things motivated a Habsburg Archduke to parade himself and his nation’s power in Sarajevo, whose death in turn triggered the Great War that would divide the lands that still remained under Turkish control.

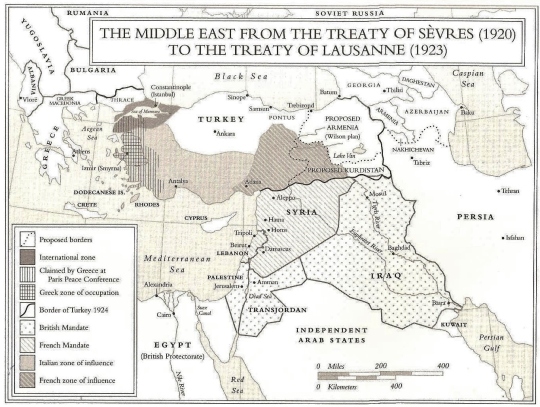

The First World War severed the Arab provinces from the sultan’s grip. Ironically, early twentieth-century Arabian warfare was remarkably similar to that of fourteenth-century Europe, allowing the medieval-military historian Thomas Edward Lawrence to exploit the Arabic advantages. Of course, this legendary figure did not engineer the Arabic revolt on his own, his own account of the events in The Seven Pillars of Wisdom, was admitted to be part myth. Furthermore, the Arabs would not get what they had fought for, as the ever imperialist states of Britain and France would divide the Middle East between themselves. This, after-all, was inadvertently why the whole war had begun.

Lawrence’s companion, Prince Feisal, spoke to the delegation in the Paris Peace Conference while Lawrence translated. They must have looked an odd pair, especially the Englishman who had donned the white robes and gold sashing normally reserved for a senior sheik. Feisal said that the Arabs wanted self-determination, and while he was prepared to exempt Lebanon and Palestine from this demand, the rest of the Arab world should be given independence as the British and French had promised. When the French reminded Lawrence that their forces had fought in Syria during the crusades, Lawrence replied: “Yes, but the Crusaders had been defeated and the Crusades had failed.” Against the wishes of Lawrence and the Arabs, Britain was also determined to get a piece of the Middle East. Forced to prevent the non-colonial aspirations of the American President Woodrow Wilson by co-operating, the two imperial rivals came to a quick compromise; Britain would get Mesopotamia (Iraq) and Palestine, while France would get Syria and Lebanon. The Arabian Peninsula did not concern the imperial powers much, probably because all those ‘miles of sand’ were not of much value at the time.

The British motives were clear. For long they had supported the Ottoman Empire to keep the eastern end of the Mediterranean safe for their shipping, but now they needed an alternate hold in the area. This motivation highlights the geopolitical value of the area. Where once the Muslims had dominated the Silk Road which provided medieval Europe with eastern riches, now the British needed to protect its trade route to India. Of course, the Industrial Revolution had created new interests in the area’s oil, but the old geopolitical motives persisted as well.

Constantinople was promised to the Russian Czar at one point in the war, but the concessions made by the Bolsheviks cancelled that agreement. While the once-great Ottoman Empire was divided, Constantinople would remain in the hands of its owners since 1453. It was occupied by the allied powers (unofficially at first), but this would not survive the determination of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk. Remarking at the presence of allied warships in Constantinople’s harbour, he proclaimed: “As they have come, so they shall go.”

A modern Turkey would rise from the ashes

As a young officer in the Turkish military, Atatürk oversaw Austria’s annexation of Bosnia, and Bulgaria secession from Turkish influence. The Balkan wars of 1912 and 1913 result in the Ottomans loss of Albania and Macedonia, and Libya had been lost to the Italians. By 1914, the European portion of the Ottoman Empire, which had once stretched far into Hungary, was almost wholly gone – all that remained was an enclave in Thrace. Throughout the Great War, Atatürk remained the only undefeated Ottoman general. His reputation was made at Gallipoli, the same battle where many allied reputations were destroyed. In his eyes Turkey was defeated not by greater armies, but by greater civilization. Henceforth, he would ensure Turkey would adopt European-style culture and politics. Indeed, Turkey remains a secular state to this day.

Atatürk sent Inonu Ismet, a trusted general, to the Paris Peace Conference to negotiate. He was instructed to achieve an independent Turkey, and as a good soldier he intended to achieve just this by any means. Turkey’s new borders included almost all the Turkish speaking territories of their former Ottoman Empire, but the fact was the empire had ended and a new very different state had been birthed. It was truly the end of an age.

Works Cited

Anderson, Scott. Lawrence in Arabia. New York: Random House, 2013.

Kaplan, Robert D. The Revenge of Geography. New York: Random House, 2012.

MacMillan, Margaret. Paris 1919. New York: Random House, 2002.